A Nation’s Standards - Part 2

‘So you see, Miss, we’re doing our best, afore she comes, to—’ At this moment Five, who had been anxiously looking across the garden, called out `The Queen! The Queen!’ and the three gardeners instantly threw themselves flat upon their faces. There was a sound of many footsteps, and Alice looked round, eager to see the Queen.

‘So you see, Miss, we’re doing our best, afore she comes, to—’ At this moment Five, who had been anxiously looking across the garden, called out `The Queen! The Queen!’ and the three gardeners instantly threw themselves flat upon their faces. There was a sound of many footsteps, and Alice looked round, eager to see the Queen.

First came ten soldiers carrying clubs; these were all shaped like the three gardeners, oblong and flat, with their hands and feet at the corners: next the ten courtiers; these were ornamented all over with diamonds, and walked two and two, as the soldiers did…

The English are a martial race and yet, they are neither a hostile nor a warlike people. True, their history revolves around preparation for war and honoring a disciplined military tradition but they have mostly used their force for either global balance of power or enforcing lucrative trade policies. In any case, they have been far more at home using diplomacy and pecuniary incentives to influence world order.

This may be why we enjoy the English gentleman as an image. He uses his intellect in parliament; language and the lilt of his voice are his finest weapons. He discusses, he negotiates but force is unthinkable except as a last resort. He is the ultimate executive and his power emanates not from the barrel of a gun but from controlled or restrained movements. Because this restraint is both unnatural and hard to teach, when accomplished, it is awe inspiring. The qualities and principles of restraint are echoed visibly by choice of necktie. Empires rise and crumble but the Englishman never deviates from jacket and tie; restraint, restraint, restraint. And this power through restraint, compressed into the small bit of silk that comprises the necktie acts like a standard of influence telling the world what “regiment” he belongs too and how he conducts himself and ultimately them.

In their own words the traditions and trends that the English tie industry sees in their country.

John Francomb, English designer

Ties are woven, rarely printed, never cartoon characters. Regimental stripes are very popular at the moment. Regimental stripes but not from actual regiments. As the club tie specialists in the UK, they have the archives of all the regiments and clubs so they can easily avoid offending any organization.

The neckties have a lightly pressed lining which leaves rounded edges rather than hard creased edges. This produces a fuller knot and dimple. It looks more luxurious this way and imparts a sense of prosperity to the observer. They sell about half a million ties a year mostly in England, so they’re doing something right.

Harvie and Hudson

Harvie and Hudson says that for neckties, dots should be no larger in diameter than a centimeter and often half that size. Navy and pink, white, yellow, red, or blue dots are most popular, and bright red with a white or blue dot. The fleur-de-lys or Prince of Wales feathers is an evergreen pattern that never really goes away. Woven ties usually come in navy with either red, blue, pink, white, yellow, sky blue, aqua or lilac designs on them. Sometimes they will form combinations, red and blue on navy, pink and blue on navy, yellow and blue on navy ad infinitum.

Printed ties in a heavy weight are acceptable with the younger set, while the older men almost always choose woven.

Drakes

The English either choose the most conservative ties imaginable or some of the craziest patterns possible. It often seems they are in a race to find ties that fit as many colors on a necktie as possible without clashing. There exists nothing in between these two extremes. This is quite possibly because the English wore such restrictive ties for so long that they lost their way taste-wise when they felt the need to branch out. Much of what Drakes does is try to find a sophisticated middle ground in tie patterning and coloring that will still embody a distinctive English flavor and tradition.

Henry Poole

Paisley ties are mostly for the country and unite the subdued elements of the country outfit of tweed jacket and tattersall shirt. Poole carries a selection of ties that it knows will appeal to its English (or anglophile) clientele. The background colors of the silks are mostly a medium navy and a dark red.

New and Lingwood

Wool ties, madder ties, knit ties are all popular. Ties are not mandatory, as they once were, and have been reinvented a bit for survival purposes. They’ve become more colorful and the challenge is to offer this without offending English tastes, and include textured plain ties and semi-plains (small dots and geometric designs).

Their ties with a different front and back blade color exemplify the sort of hidden difference the English find attractive. Small neat and small paisley designs go back deeply into the archives. The silk is in a particular type of finish. Vanners make excellent silk for neckties and they buy a lot of fabrics from them. A company called Adamley is used for printed tie fabrics, and Thomas Mason fabrics for shirts (they aren’t owned by the English but still demonstrate English tastes).

They make ties with a contrasting rear blade. That achieves two ends (ha-ha) first the tie is something that identifies the wearer of part of a set that shops at this exclusive store and second, the tie has that subtle nuance that can only be glimpsed at certain times which the English find titillating.

The mill of Vanners hold the secrets of the English art of silk weaving.

Turnbull and Asser

Turnbull make a large selection of ties which are a sort of highly refined City Lad approach. Truthfully, they are also well loved by barristers and bankers, mandarins and the heads of the larger corporations too. Turnbull employs the colors and patterns that the English hold dear in a riot of acceptably native color combinations. The ties themselves are a brand recognized by most men in England and carry their own unique cachet. Many of them that seem new and fresh are designs harkening back to the Swinging London of Carnaby Street.

There is a huge trend toward woven ties in England. Red is popular, but the national passion (which is rather cool) is all shades of blue from a royal down to a navy. A navy solid with a herringbone pattern is the one they would stock most to appeal to English sensibilities.

Vanners

One of the traditional ties in England is the regimental tie. The market for regimental ties endures globally, even if it has cooled a bit in Britain. Quirky color combinations are acceptable. The regimental tie industry is based on two simple striped patterns: the Guards stripe, evenly spaced inch wide stripes of color one and color two, and the club stripe, composed of a quarter inch stripe on a dark ground such as the “Old Etonian,” which has a navy blue ground with a sky stripe.

It should be mentioned that although certain stripes are called club stripes and are used by clubs, the actual club tie or heraldic ties are those with small repeating motifs ( a fox head or a rose for example) or escutcheons (School or association coats of arms) on them.

There are also grid patterns and geometrics. These are self explanatory.

Macclesfield tie patterns are small neat designs sometimes but not always in classic color combinations. And what is a Macclesfield tie pattern exactly? During the first half of the twentieth century, the two powerhouses of English necktie silk weaving were Sudbury in Suffolk, and Macclesfield – both industries being legacies of silk weaving from earlier centuries. During this period jacquard tie designs were either stripes (including regimentals), or small scale jacquards. These jacquards tended to be neat geometrics and very small floral effects – and although they were woven in both locations, Macclesfield became pre-eminent in their production. To this day, therefore, small neat jacquards are still referred to as ‘Macclesfields’, especially when woven in classic colourations.

Another typical scene at Vanners where silks undergo a series of treatments before they are woven into patterns.

Duchamp and Richard James are two houses that have created a new direction for a certain type of woven and very colorful tie that appeal very much to the English taste. It is difficult to put a busy tie on a busy shirt, but the English will do it. Vanners weave Duchamp’s and Richard James’ tie collections and appreciates each firm’s unique and exciting approach to color and pattern. This enthusiasm translates into a better all-around product because both sides (designer and weaver) participate in the color riot, making these ties uniquely English.

They also make the silks for the Turnbull and Asser and the Charles Hill silk ties, which posses a color value that is difficult to achieve elsewhere. The same could be said of the ties carried by Thomas Pink, whose Madison Avenue store is very large and showcases a lot of Vanners’ silk weaving handiwork.

The English enjoy color on their ties, even if the background is often dark. Men in England tend toward blue shirts and navy blue ties. Navy background with white or pink or red is a natural design starting point for the English market. Vanners has at least 20 shades of navy from a sub royal blue to a blue/black. Navy background neckties are in such demand in England that they could easily create another 20 shades. After navy, wine backgrounds are next on the popularity scale, followed by a buff color or a yellow/gold.

Beautiful colors are the result of painstaking attention to detail. Vanners’ collective knowledge produce the shades the English find desirable.

English men are not afraid to wear pink or orange as a background color or as a highlight. Actually, as Shakespeare’s Herald alluded to in Henry V, Englishmen are not afraid of anything at all. But more to the point, they certainly are not afraid of colors nor do they shy away from clashing tie and shirt. Clashing colors isn’t a concern because the English see it done so often by their men that it has become “classic.” On the upscale websites or in the better English male style catalogs, the designers take great care to match ties to shirts because the rule of thumb is that ties drive shirt sales. It serves to demonstrate an ideal to the English of how colors can work together, even if the combinations work better in theory than in practice. Which is why colors of a certain tonal range can be deliberately intermixed and the result will, at worst, be a sort of quirky personal style.

Because the English have such dull weather, they tend to sport brighter colors for accessories; they need to cheer each other up.

They don’t wear the wedding ties that Manhattanites wear on a regular basis. They do wear them for weddings in shades of grey and also lilac, blue and pink.

More than 50% of the ties sold in the world are bought by women on behalf of men, and so design aesthetics are created with what captures the female eye as well as that of the male.

The English put patterns on patterns all the time and they put patterns of tie on same scale patterns of shirt without any regard for the result. Aesthetic objectivity is not something to achieve for an Englishman who can get more points for doing it wrong and thus appearing not to care at all.

In America the number one background color is red, followed by black (which the English don’t like much, but this is changing). Americans match their ties to items other than their shirt or with regard to the entire ensemble of suit, shoes, pocket square etc., while the English only match their ties to their shirts.

Over the past 5 years their colors have come up in tone. There is greater demand for brighter, cleaner shades than before with firms like Duchamp and Thomas Pink driving an appetite for pure, primary tones of color.

The English prefer chunkier, heavier weights with interesting weaves and tie constructions . Texture is important, and stiffer, crisper silks are in ample evidence in the English market in distinction to the softer, gummier, drape-y ones so popular in other markets. Simply hold a skein of English woven silk and you can feel the crisper handle. Why is English silk different? English tie silks are said to have scroop1 , part of the silk weaving and refining process. When made into a necktie, scroop gives off it an almost audible “crunch” as you make a knot.

Pattern setting is both a technical and historical art form. As such, Vanners is certainly a British national treasure.

The English have a long standing tradition of producing jacquard silk weaves in a large number of variations. In fact, they have developed so many acceptable textured weaves that no man could ever wear them all in a lifetime without being a dedicated clothes horse. This art of jacquard silk weaving explains the English fondness for textures on neckties; even (or especially) on solids. Contrast this against the plain twill solids acceptable in other markets.

Skews (color ways for each tie pattern) are needed aplenty for ties in every collection. If a shirt collection features 50-100 different shirt designs, multiply that by 10 for the number of neckties needed to accompany them.

Skews or small rectangles of a tie design in different color ways are sewn together into quilts to give a potential customer an idea of how a range will appear.

Consumer demand for ties by tends to be voracious. And, creating still more demand, tie designs even for the relatively stable English typically last for only one season and then new patterns are introduced with new color ways. The good news is that Vanners can refer to their vast archival designs both to reintroduce them and to use them as a starting point to design new patterns and color combinations. As always, what’s old is new.

Vanners refers to archival books of tie patterns in order to come up with new designs several times a year.

Over 100,000 designs reside in Vanners archives, which are catagorized by decade, by pattern and by weave. These are the seeds for any Vanners project. The amount of work necessary to create a given tie collection can be vast, and many of the simple tie patterns that people take for granted required someone at Vanners to set, perfect and put into differing color palettes. Add to this the marketing schedules for father’s day and Valentine’s Day, the tie designers are working round the clock to meet demand.

350 thread count (per inch across the warp) ties exhibit the truly unique, rich quality that Vanners are known for. The warp is the thread on which the fabric is woven; the underlying basis of the design. Generally, the richer the warp, the richer the fabric.

And weave settings can make a club stripe in a “fleshier” texture, a satin stripe on a repp ground, a twill stripe on a basket weave ground. Weave settings can also account for more open weaves like grenadine or tighter, crisper weaves like the panama — the number of combinations is seemingly unlimited.

Cravats

Cravats make ties for stores like H. Herzfeld, J. Press, Dege and Skinner, Harvie and Hudson amongst many others. Very English, very knot and dimple friendly in construction. They have been in business for roughly 55 years. Their current proprietor, Mr. Norman, who traces his lineage back to the conquest, is about as English as one could hope for, in the best possible sense. Because he sees trends in selections both in Britain and abroad, I was fortunate enough to hear some of his thoughts on the English preference in neckties.

For casual the English gentleman might wear an ascot or cravat under his shirt. However, he would wear a classic tie with a suit. A classic tie is one that no one will find jarring the first time they see it. Small dogstooth or houndstooth checks, a polka dot or a plain tie with texture in the ground are examples. Grenadine ties are very popular in navy, royal, red, cream. Cream ties for a cotton suit in beige with a pale blue shirt and a cream grenadine tie. Not very City, but then Britain is a greater place than just London, and the 2006 summer has been brutal.

The English prefer blue followed by burgundy. The blue ties would be dark but not too dark. A fleur de lys tie, navy ground with red, blue, pink, lilac, aqua or gold fleurs is considered quite staid. The pin dot (very small and often closely clustered), the Churchill spot (about the size of a paper hole punch), and the one cent size which is not hugely popular but much more popular in Britain than anywhere else.

Neckties in 350 count silk, woven by Vanners to Cravats specifications. They are then made up by Cravats and appear in the very best English men’s shops, such as Harvie and Hudson.

The bowtie wearer in England will always be looking for something different. Bow ties tend to be more flamboyant and more eccentric and, once you dare to wear a bow in England and outside the Clubs — you would be hard pressed to find a bowtie wearer in London — absolutely anything goes. Much more common in England is the black tie for evening. Black ground ties are not popular in England but navy, burgundy and purple backgrounds are popular.

Pink, purple, gunmetal grey and even a blue-grey will serve as background colors but it is navy with highlight colors white, silver, pink, lilac, purple, red, yellow, sky and aqua that is king in England.

The pig motif represents the male chauvinist cult which Englishman enjoy being a part of.

Made up for Ede and Ravenscroft, a City of London based shop: a checker board motif a quarter inch across, which are even worn by the very straight and narrow London barristers, solicitors and judges in alternating silver and colored checks. Although the origin of the checkerboard motif is uncertain it is very English going back to patterns in Celtic textiles in pre-roman conquest days.

The English tie business is 90% woven and the rest is bought by foreign passport holders.

The English wear blue or blue pattern shirts and sterling cufflinks which explains their predilection for navy or blue ground ties.

They do a 50 and 36 oz printed tie, and of course they make a meal of the Vanners 350 thread count wovens which the English go mad for. They make up English ancient madder ties, wool challis ties (popular in the States because we think the English wear them, which they really don’t), Mogador, satins, repps, spots, paisleys, neats, printed to name a few. They get many of their silks designed and woven by Vanners, a firm that understands the English cultural approach to silk color, texture, pattern and weight. Designed by, for and made in England; it can’t get much more authentic than that.

Another 350 count tie woven by Vanners, made by Cravats and worn by London’s sartorial elite. The English like dense woven ties with texture and just the proper glint to the silk. The ties are between 145 and 147 cms in length and the width of the blade is between 9.5 and 9 cms.

… and for bowties

Anything goes for bowties, absolutely anything. You’re meant to be an eccentric if you wear a bowtie and thus the regular necktie guidelines do not apply. Barristers and medical consultants are often the most influenced by this look. Additionally, the most tedious and straight laced occupations generally have the loudest bowties which is why some of the nicest are produced by Duchamp, Turnbull and Asser and Paul Smith. I think it not unlikely that the English would use Charvet bowties an awful lot as well.

A short word on placing ties on shirts

Remember that the English like simplicity. This is a baseline but it is not where the entire population resides with regard to tie selection because the English also like color. At its most callow and yet culturally acceptable level, the English will place a blue tie upon a blue striped shirt and a purple tie upon a lilac striped shirt. That’s not too exciting but it is very English. At a step above this is a level of Englishman who will only place the blue tie on the lilac striped shirt and the purple tie on the blue striped shirt. This level of Englishman will never place like color tie on like color shirt and would tell you that the matched color level is indicative of a less sophisticated Englishman. However, they will still accept the practice as comfortably, if unfortunately English.

Although the English like contrast with the tie generally darker than the shirt, there are exceptions like the example above. There are no hard and fast rules about this and each combination must be examined on a case by case basis. This is the Harvie and Hudson look with a smart City twist.

Another type of Englishman revels in the clash of colors. This is the approach that he just selected whatever tie was at hand and threw it on the shirt, irrespective of its complimentary values. Buying whatever shirts and ties you like separately enhances this look which it can be said no other jacket and tie wearing set do with as much aplomb. The English love to plan it all to look like they got it wrong and still have it look “English”. These men will place their regimental or club tie on a shirt regardless of the colors or pair a blue and pink checkered tie on a blue shirt with a red highlight — close but no cigar, and yet one of the crowd.

There is yet another level that may introduce colors that neither compliment or match but contrast and also have accent or background colors that may be a bit renegade or naughty such as green, brown or orange. If this is planned with enough cleverness, the discordance is a sign of even more sophistication through the pose of “I don’t care”. This is the aristocratic stance that the English still find to be a sign of importance. However while they may be seen to be violating color or pattern taboos, they are choosing them with some care and through the eyes of a greater England. Only the English can make the right (but wrong) tie choices and still be viewed as English by their peers. An American doing so would be spotted at once.

Whatever type of Englishman you observe he will have matched or not matched his tie only to his shirt without regard to anything else in his outfit such as jacket, pants, socks or pocket square.

Ties for the English serve an interesting duality. On the one hand, they are mere napkins which protect the shirt. Well-to-do Englishmen will buy ties in polyester because they are washable! Something an American of the same background would find hard to fathom. On the other hand, there are messages sent by the choice of tie. Different sorts of Englishmen choose different colors and patterns and within each clique there further exists a hierarchy of who everyone is according to the choice of their tie. There is thus their group and our group, but then there are also judgments made about everyone within a given group. The serious man picks the darker, smaller pattern, the womanizer may choose louder ones, and the thug may pick a different sort of tie again, but all bought from the same shop.

I recall old movies set in the colonial era where it was a disgrace for the British regiment to lose their ensign or even let the flag touch the ground, embodying as it did regiment, queen and country. Similarly, the necktie announces who the wearer is and the position he holds in the regiment that is England which as a consequence sets a nation’s standards.

1 the crisp rustle of silk or a similar fabric.

A Nation’s Standards-Part 1

`Would you tell me,’ said Alice, a little timidly, `why you are painting those roses?’

`Would you tell me,’ said Alice, a little timidly, `why you are painting those roses?’

Five and Seven said nothing, but looked at Two. Two began in a low voice, `Why the fact is, you see, Miss, this here ought to have been a RED rose-tree, and we put a white one in by mistake; and if the Queen was to find it out, we should all have our heads cut off, you know.

And England has always had a love affair with roses. They had the Wars of the Roses1 with white and red roses used as heraldic badges to distinguish political factions. Roses figured prominently on the long banners used during the period and became the symbol of the Tudor dynasty that prevailed at the end of this conflict. And like the deepest fear of the cards Alice meets in the flower garden, a lot of the nobility were beheaded for choosing the wrong colored rose2.

During the Wars of the Roses, heraldry and livery3 reached their zenith with the English grandees spending unimaginable fortunes to outfit their retinues in the colors and symbols which echoed their crests. The point is that the English believe in symbols and their whole culture has carefully cataloged their rules and meanings. When men stopped wearing identifying badges directly on their outer garments or carrying shields, it was natural that the necktie would devolve into a form of personal crest.

Without getting into the evolution of the necktie, suffice to say they were almost universally solid bits of silk with a functional use to protect the shirt and hold the collar in place. I suppose after a while, someone, somewhere4 became bored with the universality of solids and the small pattern was born. It probably should have stopped there but the fact is once that cat was let out of the bag, it was impossible to stop the proliferation of patterns that eventually produced the harlequin prints of the 1920s and 30s5.

The necktie itself only achieved its current four-in-hand shape around the same time that patterns began to appear. In the twentieth century, English heraldry entered a new more bureaucratic age and personal crests gave way to those of military units, schools and political organizations. Even if they secretly desired them, men did not need special and unique ties because it mattered more to be recognized as a member of a powerful group or to express exalted indifference to the same. The age of the peer stamping his own badge on everything was at a temporary end and now it was all about the regiment, the school, the profession or geometric nothingness6.

But irrespective of the purpose of the necktie, whether to complete the outfit of jacket and shirt, a signaler to an observer or even to reign in a man’s behavior, it has to be made of some material and silk with a wool lining has been the most enduring choice for English men. They prefer a heavy, solid woven silk which yields a chunky sensation when handled. This is appropriate really because the English engage in what I call Chunk dressing. What does that mean? Good question and since it is based on my observations and interpretations I suppose I had better tell you.

Chunk dressing is an approach. Items are simple in both color and color combinations, patterns can be quite bold and contrast is apparent. Additionally, items of the same scale of pattern and groups of color are lumped together irrespective of “clashing.” It works well under certain guidelines because the colors are all of a sort. City colors go with city colors and country ones with country ones.

These spotted ties all illustrate both the simple primary color rule and the chunky, rich silks the English prefer for their neckties.

The fact that colors tend to be simple and primary means that there will be a certain harmony to the cacophony of pattern and color…if you see what I mean. Bear in mind that chunk dressing allows a certain weight and quality to become the standard. Interesting factors such as the mildness of the English climate allow for a uniformity of texture and depth throughout the outfit, throughout the year. It would be hard to imagine a Manhattan-ite going to work in 100 degree August weather with a heavy woven tie around his neck.

Another example of simple, primary color combinations.

This uniformity of tie thickness (both silk and lining), tying its thicker knot translates into other uniformities in the English outfit such as a single reigning shirt collar style or at least a relatively minute degree of variance within the world of the spread collar.

It would be hard to wear a straight or forward shirt collar with the chunky ties most Englishmen own. Although straight collars are actually quite common in England and though predictably crowded by the fuller tie knots, it does not look THAT wrong.

The English do not like having to deal with what tie goes with what shirt collar. And the basic outfit uniformity expands like a mushroom cloud until the basics of cut, color and quality are all similar enough that distinguishing elements lie in how you wear something, not within what exciting choice you’ve made. That’s why we as Americans see only a color or a pattern while the English see a specific knot for a tie, the bend in a collar, the way a shirt cuff has been pressed. Sherlock Holmes’ solving mysteries through use of deductive reasoning via observation is more than a good story; it’s the way the English mind works.

Frequently you will see that neckties and shirts are very straightforward. The colors and patterns used rarely have a Byzantine intricacy that can be found in other cultures’ patterns. Colors are simple and pure rather like the basic set of Crayola crayons. Suits are dark, shirts are light and ties are dark (but rarely as dark as the suit, oh la la!). To be sure the whole English ensemble works well if kept within its confines and explains the limitless variations on the same theme. It’s important to understand the ties that bind the English. While it might seem that anything goes, this is not the case and even neckties worn for a flight of fancy are actually chosen for subliminal cultural reasons. It would seem that with regard to necktie selection, the English are much more repressed than some other jacket and tie wearing cultures.

The English consider the Shirt to be the important thing, even if it’s quite bold and the tie is the equivalent of a napkin. In the States, we consider the shirt akin to the palette where we showcase the all-important necktie. However little an American may know about clothes, he will wax nostalgic about his choice of neckwear. In England, shirts are trusted friends and certain colors and patterns that we would consider dizzying serve as British classics.

But why are there so very many English shirt classics and why are a large proportion of them so bold and open to minute reinterpretation along the same theme? The City of London is a single square mile of financial services territory which supports some 400,000 commuters every overcast day. Many of them will qualify as the City lads who favor brash shirts, something no doubt to admire on themselves and each other while they spend most of their day on the phone or watching the ticker. The point is, you can often look at your own shirt, but once it is around your neck, it is harder to visually enjoy your tie. The deeper point is that with so many shirt and tie wearing Englishmen concentrated in a small arena, one needs an awful lot of classic shirts to be in step with tradition and still look a bit different from your neighbor.

We are speaking of trends here. There will be things that appeal to everyone and those that are not worn but are unobjectionable to anyone. However, at the ends of this scale there will be those who will wear only the most restrained of things and those who will dress flamboyantly or with more panache. There are shirt and tie items the general office worker would never touch but will still either admire or sneer at as fundamentally an English choice as opposed to that of an outsider.

But what of the ties? If the controlling word for a film and its cult following which resonates still through the decades can be summarized as “Plastics”, then too can the defining word for the choice of English neckties monolithically define itself as “Geometrics”.

And there are three genres of ties, the very staid old Tory tie which is the bulk of the Drakes7 style prints and wovens, the Turnbull and Asser-esque tradition which has been taken up by TM Lewin, Harvie and Hudson and dozens of other merchants and makers, which features large two- or three-color geometrics, with the spot tie being the most popular, almost always on a dark blue or red or scarlet background with a contrasting spot. Finally there are the very bold ties of a Duchamp, which combine dandyism with abstract art.

Color and Tone

Americans- at least those among whom I spend most of my time- tend to be as conservative in their clothes as Londoners. There are, it is true, certain subtle distinctions between the two. A friend of mine from the eastern seaboard, a tall upstanding gentleman whom I have always regarded as more British than the British both in his apparel and in his accent, was in a London club one day, waiting for a member who had invited him to lunch. As he stood at the bar he overheard three young men speculating as to whether he was an American or an Englishman. He could not resist approaching them with the question, “Which do you really think I am?”

Two of them replied that they thought he was British. But the third dubbed him an American. Asked how he had come to this conclusion, he said, “Because of your tie.”8

“You have ruined my life!” my friend exclaimed. He had thought this tie of his to be of the discreetest and most British design. Now, whenever he goes to London, he finds himself looking curiously at every man’s tie before he looks at his face, trying in bewilderment [to figure out] just how he went wrong.

However formally they may be dressed, Americans do tend to wear brighter ties than the British do. They also wear, rather more often, their own version of the Old School and club ties.

… excerpt from Windsor Revisited by HRH The Duke of Windsor.

The one starting rule is that for work, the English, at least when in England, like dark ties. Medium blues and bright reds are acceptable, but generally dark ties are preferred. This is interesting if only because one would think a tie is a way to introduce some glint and relief to the dark suit and dry shirt. However, that is an Americanism. The English introduce light and color through their shirts.

And speaking of color, one must choose dark blue ties that are not too dark, lest they match your navy suit too closely. To be clear, “dark” does not mean an absence of brightness or vibrancy, although it often does. The English have no reservations about rich, deep color in their tie, and colors are often both purer and contain various shades of the same color to give warmth to the visual effect. For example, consider 4 different shades of blue, all pure in their own right, woven into a tie to keep the overall effect a true blue from a distance, but closer inspection reveals the gradients of the same color.

In England, contrast is king, ties should be darker than shirts and their background color should never match that of the suit.

But if the English like dark ties, why then do they often wear pale ones? It might be closer to the cultural truth to say that they are expected to wear dark ties rather than that they like dark ties. As such, the Englishman, by wearing a lighter, brighter tie, is in a perpetual state of naughtiness; a form of sartorial derring-do. Not only does it help brighten up the frequently overcast weather, but also serves as a way to bend the rules without breaking them and so fulfills an English penchant for sartorial deviance.

As mentioned, the English will wear bright ties as long as the color is true and pure and not washed out. Occasionally a bright pink or orange will light up an otherwise sullen worsted navy suit, but the color resolution must be strong. Black ties and black background ties cannot be given away. Although, having said this, black ties are beginning to make headway with younger dressers. For the moment, if you had to buy ties for a shop catering to English customers, you would do well to avoid black.

Think of the large number of exceptions in this way. If you are American and I were to state that most American men wear a white or light blue solid shirt for work, your mind might instantly attach to the large number of examples on a given day where this is not true, ignoring the even larger pool of men who are indeed wearing white or blue solid shirts. The exceptions do not disprove the rule.

Bright ties are not a problem for the English. Notice that these ties, even when they appear busy, are all very simple.

In the USA, bright or light ties are common but there is a dislike of dark ties as overly mature and serious. Thus, an American who sees a Brit wearing a light tie registers it as normal and does not detect the flamboyant bravado the Brit believes he is displaying to the world. The message is lost on us, and lost more deeply because so many Brits wanting to be dashing wear the brighter tie. But in the overall context of English culture, it would be viewed as a renegade look.

Unless it is in a regimental or club pattern, black is out. Dark grey, dark red, dark blue (but of course not the darkest blues because that would make it all too easy to sum up), dark purple (although not too dark lest you give the impression of “assuming the purple”), dark green (not a forest green but a rich dark emerald) with the operating term being dark. Why not lighter ties? It seems there is a real anxiety over being mistaken for an ice cream salesman. The vast majority of lighter ties the English make are sold overseas.

In fact the number one seller in England is blue of one shade or another from medium to the lighter shades of navy, followed by dark red. So forget about all those shades of yellow, pink, bathtub green, lilac, sky blue, cream etc. you see with English labels on them. Those are all made for export.

Patterns and textures

Woven ties are preferred in England. In the USA, prints are also somewhat popular. Our brutal summers give rise to the demand for something lighter and more carefree wound around the perspiring necks of our miserable office denizens. A printed tie is more in keeping with the spirit of the heat wave. This is one reason we like lighter colors for ties that the English will gladly export but wouldn’t acquiesce to wear even at gun point.

Although the English will wear printed ties, they prefer ones in heavier weights or with thicker linings than are normal in the USA. They also like a very bright red background in prints. I have seen the English wearing all sorts of ties, and they are far from infallible in their tastes. They wear ties of every color, weight, weave, pattern; they even wear ties that match the color of their shirt, which cuts against the grain of their usual principles of contrast between shirt and suit, and shirt and tie. Of course, this discussion is pertinent to trends and traditions, not what each and every Englishman wears.

When the English do wear printed ties, they prefer heavier weight silks with texture.

Solids you should think would be the off-the-rack choice for a mindset that reaches for heavily patterned shirts, but that would be far too easy. The English do wear solids but generally consider them uninteresting.9 Solids themselves need to have some texture like an ottoman or panama weave or even grenadines. For solids, the English require an interesting look, which is why the satin finish (and the Mogador) is making headway. Satin finish ties, when nice enough quality densely woven from expensively dyed silk and, ironically, somewhat matte finished, combine surface interest with intensity of color. The sort of solid tie American men like, the basic flat looking solid, is avoided in England.

Popular are the Sheppard’s check or hound’s-tooth ties in a variety of scales from tiny to the size of a nickel, either in the self color (making an interestingly textured solid) or in a contrasting color, silver and navy, purple and black (or is it navy?) etc…

The English see details. It is likely that Beau Brummel’s focus on details as the mark of quality in otherwise plain clothes was nearly as compressing as the force required to turn coal into a diamond, then you start to understand how small variations on the same theme impress the English.

Here is an English “curveball” to consider. To my eyes, if something looks handsome, it is acceptable. Generally it will also be admired as handsome by my fellow Americans and accepted as such. To the English, something that looks handsome can still be culturally awful, and it might be admired but you will be an outcast. For instance and although you can learn to mimic the English approach to shirt and tie, when it comes to socks and pocket squares you tread on perilously thin ice. Not only in the choice of material and color(s) used but in the way it is plopped in the pocket or slid up the calf. I daresay an entire book could be written on the subject of when it is acceptable to wear a pocket square and the images you conjure in the English observer’s mind. Some apparently dreary choices can sound you out as a bounder and some flashes of color can mark you as a solid citizen without so much as a warning or a reason. If someone were attempting to study the English to produce spies to mix amongst them, I would wish them the very best of luck and hope their grip on sanity was concrete.

Stripes or club ties are a national source of angst. To wear one you are not entitled to is a sin looked down upon by even those who do not wear neckties at all. The chances of making a mistake are great enough for most English men to forsake wearing a regimental tie altogether. However, it is undeniable that a striped tie is a beautiful accompaniment to a shirt and a suit; a sartorial fact that English men would admit to. How then do we reconcile the social barrier with compelling sartorial art? Enter TM Lewin, keepers of the English club tie for nigh on forever. They know and archive every club tie in existence that rates in England and therefore they can produce regimental tie patterns that infringe on no one’s right to be an old boy. An interesting “blue ocean”10approach to creating a new, untrammeled and in-demand market. That’s Capitalism on the hoof.

Striped ties often have texture as do solids. The English do not generally like smooth ties unless the silk has an interesting finish.

End of Part 1

All ties by Harvie and Hudson.

1 The Wars of the Roses were a series of civil wars fought in medieval England from 1455 to 1487 between the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The name Wars of the Roses is based on the badges used by the two sides, the red rose for the Lancastrians and the white rose for the Yorkists.

2 Although identification of a given noble house was often easy which political faction they backed was more difficult to determine. Because the Wars of the Roses had few soldiers in any sort of uniform beyond liveries, confusion over which side one was on was a recurring problem. It was not uncommon for friendly soldiers to fight each other accidentally or for captured Yorkist soldiers to claim they were fighting for the Lancastrians.

3 Although I will assume that everyone understands that heraldry is the art and science of noble identification, livery should be explained. It is the manner in which nobles decorate and signify ownership of their property; including human servants.

4 It might have been James Lipton who liked a small repeating white dot pattern on a dark background.

5 Created and produced by Charvet they were inspired by Ringling Bros. travelling circus and soon became a favorite afterhours choice of the smart set. They combine abstract design with beautiful colors and quality silk and linings. Due to difficulties with the process, printed ties were not common during this period and Charvet’s bold patterns were seen both as an exclusive symbol of consumption and as one of leisure triumphing over labor or commerce, not to mention they brightened up a lot of mundane outfits.

6 During the war of the roses, banners and standards had been painted silk. They were always considered secondary to the decoration on the soldier or knight himself. That was a problem; in fact the main problem discovered was that the nobles had far too much power which the Tudors sought to dissolve. With the rise of professional regiments raised for the King, power was transferred to the throne and embodied by the regiment’s colors. The idea of a silk flag personifying the regiment or the country blossomed. The turn back facings of the colorful jackets were reflected in the regimental colors. The logical conclusion for an army which abandoned colorful jackets for khaki was to place the facing colors as a badge on the sleeve head of the jacket or as a flash on the side of the helmet. Neckties also reflecting the colors of both the jacket turn backs and the regimental flag were used to distinguish their otherwise standardized uniforms.

7 Drake’s are an English tie maker, and although the English generally do not like prints, they will wear them if they are heavy and rich enough and very conservative. Of course, many of the British wear printed ties outside of the City for Town or casual events but they prefer the woven ties for business.

8 Never mind that James Clavell wrote in King Rat that the English could always tell the American prisoners of war by their waxy skin!

9 Actually, Kate Fox in her “Watching the English” (p.291)mentions that the the single solid color tie is considered no higher than middle-middle [class].

10 Blue Ocean vs. Red Ocean approaches to business opportunities appeared in Harvard Business Review. Essentially the “Red Ocean” approach involves fighting with competitors over existing market share while the “Blue Ocean” approach entails creating new markets without competition.

Comment [1]

Sportswear and its Merits

As we’ve seen in The Boutique as a Sartorial Temple there had been a serious move towards a more casual street smart look since the fifties. A transposition of attire as it were.The very word sports jacket indicating a thing or two as well although it was still a long way to go to the tracktop being established as a classic.

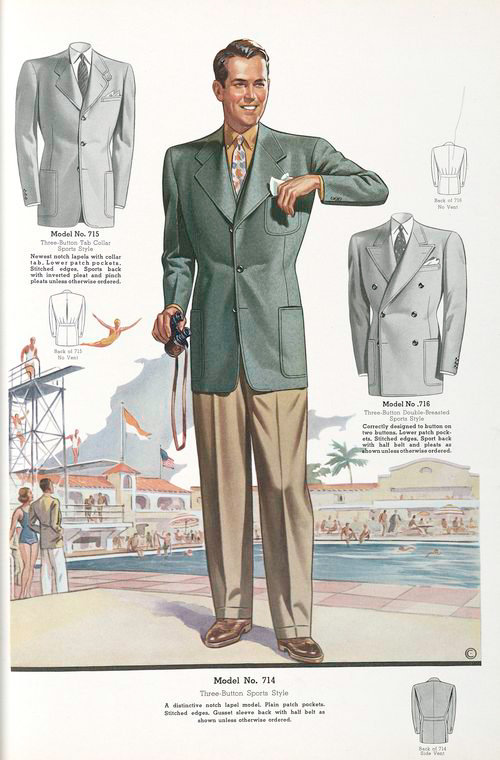

Three-button sports style1.

There is however a huge gap between what was once considered as a sporty (weekend) outfit and todays uniform of studied nonchalance. The difference is basically an attitude thing though. Whereas people before the second World War (and for some time afterwards still for that matter) wanted to look smart and tidy in sports jacket, button-down shirt and slacks, scruffiness seems to be the norm nowadays. People most definitely don’t want to come across as neat anyway. Back in the day a man wouldn’t take off his jacket too easily which should be looked upon away from convention. Even within the comfort of his own home the sake of smartness would still call for a nice sweater or cardigan to be worn over the (open necked) shirt. If one understands this intrinsic need, well, that would be a start I’d say. Perhaps in this day and age the knitwear would be a bit more adventurous so the sporty element will be a bit more prominently on show. There might even be a tiny label to spot on first or second glance (gasp).

It’s all a matter of nuance and a shifting emphasis really. A contemporary take on a classic influence, a style update which can be lifted from fashion, but that’s optional.

The same goes for the footwear. Think nice, clean trainers instead of the classic loafer for instance : Puma Clyde or States, Adidas Samba or Forest Hills, New Balance Trackster, Nike Bruin or Cortez or Diadora Elite are all great classic alternatives. Please be aware of the fact that not all re-issues are all that great though.

Puma Clyde – Olive and green. Classic Puma basketball shoe straight from the archives2.

To elaborate on this, just stop and think of the fact that the classic sports jacket will look pretty formal to the average modern eye. The wearing of a simple knitted polo shirt under a (suit) jacket will ask a lot more of the imagination to reach the same liberating effect, if you will, too. In this respect one could e.g. think of a Rapha cycling top and in doing so implementing a functional, hard wearing garment to an otherwise semi-formal outfit. The loosened tie worn cuphandle style might still carry some validity when applied imaginatively (like under an interesting v-neck and blazer combo perhaps), but you’ll get my drift by now.

Further still I’m convinced it’s next to impossible to make those of classic sartorial persuasion see the beauty of the tracktop, let alone them donning one, but as an example I’d like to point out the smart effect the following ensemble will have, once you’ve got an eye for it :

Classic (that word again) box-fresh (like) trainers, a pair of the best modern jeans there is to be found (indigo, possibly dry/raw and no distressing or other distracting, silly details), matching belt, quality T-shirt and cotton or wool mix tracktop in perfect colour coordination with those trainers. Solid colour socks too of course ; Burlington or Falke rather than toweling ones and you’ve arrived. Oh, and all this topped off with a short, neat haircut needless to say. As in a best of both worlds sort of way ; counterbalancing the overall casual presentation that is.

Fila Match Day Jacket3.

The idea of taking countrywear to the city is not a new one, indeed far from it, but it’s a core idea nevertheless when it comes to ‘Smart Casual’. Casual smart reminds me too much of a business suit worn ‘sans tie’ by the way, so the correct term would be as stated thank you very much. I do like the sound of ‘Casual Chic’ as well. It would become a bit pretentious however when used on a regular basis. Also, it’s not at all in accordance with the working class roots of the matter (tongue placed firmly in cheek). Taking schmutter out of its context and applying it to less obvious, new surroundings remains an endless source of inspiration for those into what we’ve previously dubbed as ‘Hard Dandy’.

Perhaps the biggest challenge within this approach is to make a combination of formal-, sports- and country gear work. e.g. Trainers, cords and formal shirt topped off with some heavier ‘outdoor’ knitwear (I would like to mention CP Company and Stone Island here).

Such an outfit is guaranteed to be appreciated. What makes it all most interesting, to my mind anyway, is that it is a reversed form of rebellion. Subtle, smart and sensible at the same time. The perfect look in short because it never really dates.

Another good look may consist of a sports shirt meant to be worn untucked, so that the bottom of the shirt can be seen from under a colour-wise complementing v-neck. Again, if this combination is worn in perfect harmony with some nice casual footwear, with maybe some fitted cotton trousers worn in subtle support, it may result in a very youthful look that will actually work regardless of age. And what’s more : there are so many modern classic jackets to be found in both bold or sober colours, whatever the occasion may ask for, that have a street smart appeal. Cotton/windcheater, like the Baracuta G9, waxed cotton (Barbour and Belstaff spring to mind), corduroy, denim, leather, wool, you name it. Just try on a few of those handsome numbers in front of a full length mirror at your favourite clothes shop, simply enjoy the fact that you won’t be able to buy them all and let the mirror decide for you.

Barbour International Jacket Sandstone4

Suede chukka boots with matching belt, quality jeans, plain merino roll- or turtleneck and tweed jacket with a paisley hanky is another look I rather like in a more classic framework. Think Steve McQueen in “Bullitt”. The jacket may require a contemporary touch mind, perhaps an Italian, semi fitted one or then again maybe the use of a mixed fabric would be nice.

The possibilities there are to discover through experimentation never stop to amaze me. Sartorial exploration will keep me busy until the end of my days and I suspect a few of you reading these lines will keep me company in spirit. Fellow travellers and all that.

Alex Roest

Footnotes

1 New York Public Library Digital Images

Recommended reading :

Trainers by Neal Heard

Casuals by Phil Thornton

They’ve Done Us On The Wardrobe Front pt II: Phil Thornton Casuals by Alex Roest

Comment [1]

Designs of the City

It was the White Rabbit, trotting slowly back again, and looking anxiously about as it went, as if it had lost something; and she heard it muttering to itself `The Duchess! The Duchess! Oh my dear paws! Oh my fur and whiskers! She’ll get me executed, as sure as ferrets are ferrets! Where CAN I have dropped them, I wonder?’ Alice guessed in a moment that it was looking for the fan and the pair of white kid gloves, and she very good-naturedly began hunting about for them…

It was the White Rabbit, trotting slowly back again, and looking anxiously about as it went, as if it had lost something; and she heard it muttering to itself `The Duchess! The Duchess! Oh my dear paws! Oh my fur and whiskers! She’ll get me executed, as sure as ferrets are ferrets! Where CAN I have dropped them, I wonder?’ Alice guessed in a moment that it was looking for the fan and the pair of white kid gloves, and she very good-naturedly began hunting about for them…

Even in his fearful panic, our white rabbit understands that he needs to present himself properly. This might explain an English disdain for the complex. Otherwise, one would always be late, even for one’s own execution. The English believe that roles are important and that the proper clothes announce that one authentically fits into a given role. This is why as a people they produce so many talented wardrobe and costume designers. I recently had occasion to speak with one very accomplished wardrobe designer.

Doug Hawkes – Costume Designer:

He and his wife (and partner) have worked on many wardrobe projects for shows like Brideshead Revisited, Jeeves and Wooster and House of Cards.

For a recent production, they used silk striped and polka dot linings for Peter O’Toole’s very otherwise conservative suits and smoking jackets. The linings are a bit like those Paul Smith is using at this time. Fancy vests and waistcoats for day wear are not risqué like they used to be and have entered the imagination of the conservative club land set. Younger men too are wearing fancy linings and waistcoats.

Mr. O’Toole is quite particular about his clothes and always wants a special wardrobe for his characters (which he likes to keep). He is especially interested in evening and formal clothes.

For example, Mr. O’Toole had them make a silk smoking jacket for him modeled off of an original from the 1950s, itself an interpretation of a Victorian style smoking jacket. The net result was to make the actor a jacket with more structure and more authentic styling like the original Victorian garment the 1950s garment was supposedly imitating!

I aksed some random questions about what looks produce what reactions in viewing audiences, some of his shows and what sorts of things the English like.

Natural shouldered suits or at least a more natural shoulder is more refined and gentlemanly while large shoulders are more aggressive and unfortunate.

One detail that had always seemed wrong to me was the loose arrangement of Hugh Laurie’s collar pins in the BBC/Granada production of Jeeves and Wooster. Mr. Hawkes knew exactly what I was alluding to. Apparently, the pin collars on Bertie in the Jeeves and Wooster series were too loose not because the wardrobe dept didn’t know better but because the fashion was for actors to refuse to wear detachable shirt collars too close around their neck because they felt uncomfortable to modern throats.

Also discussed from Jeeves and Wooster were those beautiful, knit country sweater vests both pullover and cardigan styles which were woven by little old ladies who understood the traditional weaving techniques and patterns. Modern knitting schools aren’t teaching this anymore. Plaid wool ties, and in particular in green are Mr. Hawke’s signature. Those plaid wool ties used in the country by male characters in Jeeves and Wooster were reproductions based on originals collected from a variety of sources.

Borsalino hats are the finest and carry a look which is plus Anglais que les Anglais. They serve well for historical productions and respond well to custom needs such as changes in crowns or brims to adjust for contemporary purposes.

Hats are just a bit retro, no? Well, that’s just it, Mr. Hawkes loves the styles of the 1920s through the 1950s with a lashing of Edwardian style.

He thinks of the English suit as the true 3 button, side vented jacket, three piece suit, fully lined with interesting pockets, pockets for watches, hacking pockets.

About the English, they miss a lot of eccentric humor and touch in clothes and décor on film for wardrobes or sets generally. Foreigners pick up the labyrinthe of elaborate clues on people or objects and love them. It’s not that the English are blind or dim it’s that they just consider it so normal it goes unnoticed. The English also tend to be more verbal than visual. It takes an outsider to admire the visual qualities of English style.

Brown suits are not popular with the English. Green is another color the English have problems with in the City. A true green stripe in a suit might evoke a wriggled up nose. However, it’s always a matter of degree with the English and if the green stripe were executed on the fabric with enough subtlety, it might become acceptable.

However, the English always consider tasteful a faint lilac or pink stripe that is pale and putty like. Also, a dark purple stripe on navy is quite rich looking. Sometimes the tone of the pink stripe appears almost orange-yellow to the eye at first glance.

After I warmed him up with some of my random questions, we decided to produce a show together, my script and characters, his wardrobe to highlight their attributes. A contemporary TV show centered on a City brokerage firm.

General costume guidelines:

For the middle managers, slightly dated three button high fastening suit with fine and subdued stripes with conventional, solid colored shirts and dark, small pattern ties or spotted ties (with the spots from 1-2 cm in diameter).

Single button heavy pin or chalk stripe suits with colorful linings and contrasting waistcoats (In a purple or pink silk maybe with a semi-crepe texture) or bold colorful shirts for the younger guys coming up. Heavy geometric prints or madder prints for ties.

For the bounder or phony, the necktie is the most use signal that he’s deceiving people by choosing the wrong necktie.

It is clear that the English do not disassociate the idea of color from the term conservative. In America, conservative is often seen as safe and drab and pattern-less. In England a rich woven purple tie with many different colored small lozenges can still be conservative.

Chelsea or derby boots (Chukkas) are a bit of the smart dresser because they allow you to wear a shorter pants leg and more of a cavalry finish.

Gieves and Hawkes would offer an example of a good conservative and upper class cut.

The different show scenes:

The first character, a powerful man at a merchant bank who maybe manages its brokerage arm his just getting off a phone call, he looks distressed. He would get a quarter inch striped shirt with a hard, spread turn down collar and a striped tie or maybe an interesting solid. Shirt stripe color choices would be: pink and white or blue and white or red and white (that damask, dusty plum like red) stripes from Harvie and Hudson.

A soft dark flannel suit with dusky chalk stripes and chunky Harvie and Hudson ties. Black Alan MacAfee or Church’s shoes. He would wear a belt with his suit, side tabs are considered more of a sports trouser. While on the phone, he would expose plain metal cufflinks in either and oval or oblong. He would have freer hair. He gets off the phone, sighs a deep sigh, pushes himself up out of his chair and heads out of his office to consult with his co-manager.

His opposite from the same background but a much nastier person apparently has had a similar conversation because he is uncharacteristically meeting the nice manager in the hallway (ordinarily, he would let the nicer manager come to him). First, to illuminate that he is more calculating and controlling, make up and hair would play a role. Shirt collars might be more angular, lapels would be more angular. Maybe a stick pin in his lapel or tie of a gold horseshoe or Fox, not strictly correct but outward, physical expression of his aggression. A sharp crease pressed in the trouser keeps the angle going up through the shirt and around the neck line and cuffs. Crisp and aloof. Oh, and slick hair.

Both of these senior guys would be wearing single breasted three button jackets with side vents in 15 oz cloths. No pocket squares.

These two senior managers complete their conversation half united in worry and half annoyed at each other. When the nice manager goes back to his office he makes a call and the first of several VPs summoned appears at his door minutes later. A guy who’s upper middle class and attended a good public school but he’s relatively uncontroversial otherwise. Navy plain two button suit and either blue striped Bengal shirt with a forward spread collar or a plain blue or white solid and a tie with a small repeat pattern on it. Black shoes, no pocket square (makes a statement in England and it’s considered eccentric).

The second VP is upper class, privileged and snotty and much more of a showoff. A stronger stripe to the navy suit, three button fastening with the higher closure. A spread collared shirt in either a white or a lavender solid. A satin finished solid tie or an interesting pattern to the solid. The satin tie yields a more interesting knot for either an Albert or half Windsor style tie knot which makes the image more suave. Silk knots for the shirt.

Black shoes, black belts for both and lighter weight suits, smoother, finer worsteds in 12 oz cloths which means our middle managers are wearing 13-14 oz suit cloths.

The third VP is a bit of a slob but still from a well to do background. We would put him in an Ecru shirt and an even lighter weight suit to ensure more creases in it for dishevelment purposes. Necktie in a four in hand knot with no dimple as if he had just pulled it through without bothering; he probably leaves his ties tied and just slips them on over his head every morning. Shaggy hair maybe an undone double breasted suit with belted trousers too tight for him and sliding below his belly.

The fourth VP fancies himself a dandy but buys the wrong sort of car and clothes. Shirt collar would be too high for his short neck, he would wear a tie with a nice dimple but the knot would be too large. Suit would have either a stripe or self stripe and would be slightly shiny maybe with some mohair in it. His shoes would be black, good quality but unfortunately duckbilled.

After everyone arrives, they discuss the looming crisis they decide that the VPs must call a meeting of the brokers. The four VPs leave the middle managers and head into a conference room. Upon entering they are met with a couple dozen chattering city lads which the camera picks up from left to right in various stages of undress with jackets on the backs o their chairs, loosened ties and rolled up shirt sleeves. They would be wearing plain color shirts in blue, white and a few blue stripes. Neckties would be very loud prints or wovens. The VPs address the city lads and fill them in on some of the goings on. Faces become worried looking.

The next scene, one of the bank’s directors and his entourage is entering the bank lobby to address the crisis with the two senior managers. He is wearing an overcoat; a slightly lighter weight and longer than normal length covert coat which he takes off and hands to a bank employee along with his briefcase. This reveals his charcoal three piece suit with a fine white chalk stripe with a single vent and a ticket pocket on the jacket. A dark tie with a small but bright pattern on a purple or wine striped shirt. Still no pocket square! Onyx on gold or on silver cufflinks. His barrister would wear a very dark charcoal suit and a pink and blue striped shirt with a navy tie with red fleur de lys on it.

Outside on the street, the head of a large media company is getting out of his car. Apparently a large story is breaking. He is wearing an overcoat in petrol blue (or chestnut brown) wool1. A very well cut double breasted suit in a definite self herringbone stripe in either navy or charcoal. The shirt would be a soft, pale blue self herringbone shirt with a grenadine tie in a red or a darkest chestnut brown. He flashes a pair of gold twist barbell cufflinks and a gold Jaeger-LeCoultre duo watch. Wearing black glace leather wing tip brogues, he storms into the bank as well.

A third man is entering the bank too. He is the scion of one of the bank’s founders and the largest shareholder. He has come up through the business. Handsome and athletic he strolls in rather confidently under the portrait of his father in the banks entry hall. His overcoat slung over his arm, single breasted three buttons, and two piece charcoal suit with a thin silver pinstripe, a lilac end on end shirt with an Eton tie sporting a four in hand knot2 and polo helmet cufflinks. Again he would have no pocket square but he would have a reversible silk and cashmere scarf (ala Alex Begg) with a modern looking geometric print on it. His shoes would be in a saddle shoe style but all one type of calf leather and in solid black.

There is a meeting and voices are raised.

In spite of the severity of the concern, there is an agreement to adjourn to get ready for a previously scheduled dinner that evening for the same characters. Set at a nice hotel restaurant. The senior people arrive directly but the city lads roll in after having stopped at a local watering hole in their work clothes. Even after hours, appearing in a pub, even a city pub, in dress clothes would be looked at quite strangely.

Most at the dinner would be wearing dark solid suits, white shirts, some of them with a self stripe and ties would vary from regimentals for ex-military men to quite bright and fancy ones for the brokers. An occasional double breasted suit and odd vest would appear.

The two senior managers would be wearing three piece lounge suits, one wearing a blue pinstripe suit, the other a slightly bolder striped shirt. One would wear a striped tie, the other a small pattern polka dot tie on the other.

The bank director and the scion would be as they were before but the media mogul travels with his own wardrobe and changed into a single breasted suit with some mohair in a violet navy, a pale green shirt in a pistachio shade with a Richard James tie in a traditional pattern with a lot of bright, absurd colors in it. He would wear the same belt he wore earlier in a black lizard.

Although he missed the earlier meeetings, the CEO of the bank makes his entrance with his wife on his arm. He would wear his charcoal herringbone with a faint grey stripe in a two button jacket slightly open with his scarlet braces showing from time to time underneath over his shirt with two shades of blue butcher stripe on a white background with a straight collar and a very boring navy tie with an almost unnoticeable pattern on it. He has just given his double breasted trench coat and his charcoal trillby to the hatcheck. As he extends his hand to shake those of the attendees, we can see his cufflinks; silver engraved with the silhouette of a nude woman.

1 Variants. He would put him in either a petrol blue coat with a brown suit or a brown coat with a blue or charcoal suit. The brown would be a red tobacco brown, maybe even with a purple stripe.

2 As if the tie said everything and the knot meant nothing.

Drake's

…and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked `poison,’ it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

…and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked `poison,’ it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

However, this bottle was NOT marked `poison,’ so Alice ventured to taste it, and finding it very nice, (it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry-tart, custard, pine-apple, roast turkey, toffee, and hot buttered toast,) she very soon finished it off.

`What a curious feeling!’ said Alice; `I must be shutting up like a telescope.’

Fear of change is with us always because change is the great foe of tradition. But there will always be that unknown bottle to try and someone, like our Alice, will always be courageous enough to do so. And, far from destroying tradition, will forever alter themselves and the world around them for the better.

Drake’s ties have braved Alice’s bottle and evolved.

The average English person might not be interested in their ties because though English, Drake’s are not typical of English tastes. Typically, English ties are either very conservative or very flashy while the more sophisticated looks of Milan and Paris are absent. Drake’s international mission is to offer English taste the way the Italians, French and Americans imagine it and offer a style that all men of taste will recognize.

Drake’s outlook is an updated version of the international look of the 1930s when men, irrespective of their origins, could admire universal good taste in a necktie or shirt on each other. It all sounds like a very exciting style but how do they accomplish it?

Drake’s asserts that the art of dressing well is incorporating something special into the outfit that the observer would not think of but would find appealing. The London City practice of matching the tie and cufflinks to the shirt is a universal starting point and beloved by the great bulk of English city workers but the most sophisticated and self assured English dressers advance past this stage. To make it clearer, the coloring by numbers approach may be England but it is the England of the tie wearing masses. The most discriminating England is one of individuals wearing smart combinations of both color and pattern.1

Caption: This is NOT a Drake’s shirt and tie combination. The Jermyn Street look of red and white striped or checked shirt and a red and white tie aren’t for him. When it comes to accessories, the English generally think that whatever is the brightest and most shocking is the best. Also English is the belief that there should be nothing fabulous about the tie sitting on the shirt, it just sits on the shirt because it picks up the same colors. Simple and safe. Branching out sartorially for most Englishmen is akin to throwing darts at a board.

For example, a brown tie with a grey flannel suit makes a man more dapper but it cuts against the grain of the standard English approach. However, a brown tie gives an outfit more sophistication and warmth when paired with a grey suit and white shirt; in summer add a tan panama hat for a real coup de maitre.

These ties are from the Drake’s Spring Summer ‘08 Collection

Drake’s offer brown woven ties in patterns that relate back to the Duke of Windsor’s times and often based on archival swatches from the period. In the past they would have been rendered in Navy (a light navy) and white or black and white (In England’s 1930s, black and grey hadn’t yet solidified a fascist association.)

For woven ties, Drake’s uses English macclesfield, end- on-end silk. Traditionally, in end on end silk, the warp is equal parts black and white with colour added in the weft usually with white crossing the white and colour crossing the black. The result is a fresh crisp pattern with clarity of design.

Perhaps the best examples of English style reside outside of the culture altogether because Mr. Drake admires the English look the way the French wear it. The French lend the English look an air of chic in a way the English rarely could; which means that although it’s all English clothing at the same time it isn’t assembled in an English manner. Is it any wonder that he admires Hermes?

Another country which aspires to English style but not the Way the English would combine it is Italy. The Italians wear the English clothes very well but they wear them precisely as items of fashion, not cultural signals. They will have none of the rumpled look the English wear so well. But then, neither will the French, Swiss or Germans and this is the divide between the familiar ease of England and the heel clicking Continent. Drake’s believe that Italy’s artistic eye enhances the English style and he draws on their dressing deportment for inspiration. And, although the Drake’s aesthetic is not Italian, they do seek to create the England that appeals to Italy’s daydreams.

Photographs from Drake’s Spring Summer 08 collection – Vintage Madders created in shades of cream, brown and blue.

Drake’s make a lot of prints in proportion to woven ties (about 50-50) which is not very English. The English tend to congregate around heavy woven ties although if they do wear a print, it will be a heavy weight silk one. The Italians like heavy prints and in terms of color backgrounds they prefer navy or blue (60%), then wines and greens and browns (20%), then everything else (20%). Italian shirts tend towards blue stripes and solids. They like charcoal and grey suits, they love brown shoes. The English wouldn’t touch a brown tie for city wear but the city lads will choose a pink tie for a change of pace.

When Drake’s design a collection they take every culture’s taste into consideration; Japan’s, France’s , America’s and Italy’s. They approach it not only from the stand point of the elegant man but also from the current of fashion. They try to envisage what sort of person would wear each tie collection and for what purpose or event. Colors, patterns and their combinations as well as what sort of shirts and jackets they will be worn with are all carefully considered to ensure the end result is not simply…ties.

Photographs from Drake’s Spring Summer collection – 50oz handprinted Foulard silk._These pastel colors are hand printed in England. They are all lined with 36 oz white silk to give them a clean, fresh look. For summer; pale blue, lilac beige, light apple green and pink and red.

Photographs of Drake’s tie archive designs circa 2004 – bondage art including intertwined whips, fetish shoes and girl with gag. All Collections have themes and although most of the ties made are geometrical, some of them can be quite whimsical such as Indian Gods, World War Two aircraft nose art, clowns and, as shown above, 1950s bondage art from period magazines.

The trendiest shops get the narrow 7cm width ties while other shops get 8 or 9cm width ties. Although for the narrow ties, Drakes ensures that the knot they make is still somewhat substantial.

Does Mr. Drake believe there a difference between a well dressed man and a dandy? There is a difference between someone who dresses in a very elegant but correct way, who does everything better than everyone else and who must have the best of every article of clothes but nothing outlandish. A dandy wears more extreme items like a skin tight jacket with a particular color shirt to pick up a particular hair color.

Drake’s do all the ties for Mimmo Spano’s shop at Saks 5th Avenue which are the best quality woven end- on-end silks with some color; the typical 1930s high luxury. It’s a chairman of the board look, very strong and definite.

The biggest single giveaway as to whether a man knows how to dress well is that relationship between suit, shirt and tie. That V formed by the closing of the suit button. A man can wear the finest handmade suit but if the shirt and tie aren’t right, it’s a sure sign that the wearer doesn’t know how to dress with panache. And the tie, like a pair of shoes, is an especially strong indicator of the taste and style of the wearer. It’s another real give away

Drake’s are the largest handmade tie manufacturer in the UK; their biggest markets are Italy, Japan and the USA. In the USA, their tie collections can be found at both Bergdorf Goodman and Barneys. The ties made for Italy have that old world English look which the Italians make a cult of and the English do not wear anymore. It’s a classic look which showcases an endless array of snowflake like patterns and the Italians cannot get enough of it. They are mostly printed on 36oz silks.

Photographs from Drake’s Spring Summer 08 Collection.

Is there a shift again for American tastes? Drake’s make a lot of ties for stores in the USA which are good for New York but wouldn’t sell in Europe. There are rules in Europe but American men are much more flexible about their choice of ties.

A machine made tie is flat and lifeless. A handmade tie2 is folding around the lining and stitched by hand for that “rounded” look which lends it liveliness and suggests quality and elegance. Of course it takes around 40 minutes of labor to complete a tie made by hand while machines can turn them out by the second.

And what is that “rounded” look? The high grade tie silk is pressed only lightly so that they make a fuller, springier knot. Does handmade make for a better tie? Everything that you do better helps the item out, and in this case hand making of the ties allows for a more luxurious item.

Drake’s has its look which can be summed up as English style with Italian artistic flair. In Italy, Drake’s are the British rock stars of tie makers. They also have a large following in Japan because it seems the Japanese love the Italian interpretation of English style! Rock on.

Drake’s own crest which his wife drew up. Cashmere goat holds up one side of the shield and inside it resides a little drake, a lamb signifying wool, a moth signifying silk, and because their Italian customers used to refer to the company as the cat and the fox, they put the fox on top of the shield and the cat holding up the other side of it.

Our hero partakes of one of his creations rather like a wine aficionado sampling in the comfort of his own cellar.

Drakes have their own web site at www.drakes-london.com

Drakes online shop is at shoponline.drakes-london.com

Footnotes